Built as a glamorous ocean liner for Canadian Pacific Steamship’s trans-Pacific run, RMS Empress of Asia was sunk near Singapore in 1942 when she was in service as an armed merchant cruiser and troopship during World War II.

Author Dan Black chronicled life aboard the liner, interviewing peacetime passengers and wartime survivors, and weaving their stories together in Oceans of Fate: Peace and Peril Aboard the Steamship Empress of Asia.

For anyone who attended Black’s book launch in the Maritime Museum of BC gallery last January, the event seemed like a homecoming: his audience was largely made up of the families and descendants of his subjects.

Sixteen people lost their lives in the sinking. Remarkably, most aboard the vessel–413 crew members and 2,235 troops–survived the ordeal.

Author Dan Black launches Oceans of Fate in the MMBC gallery in January 2025.

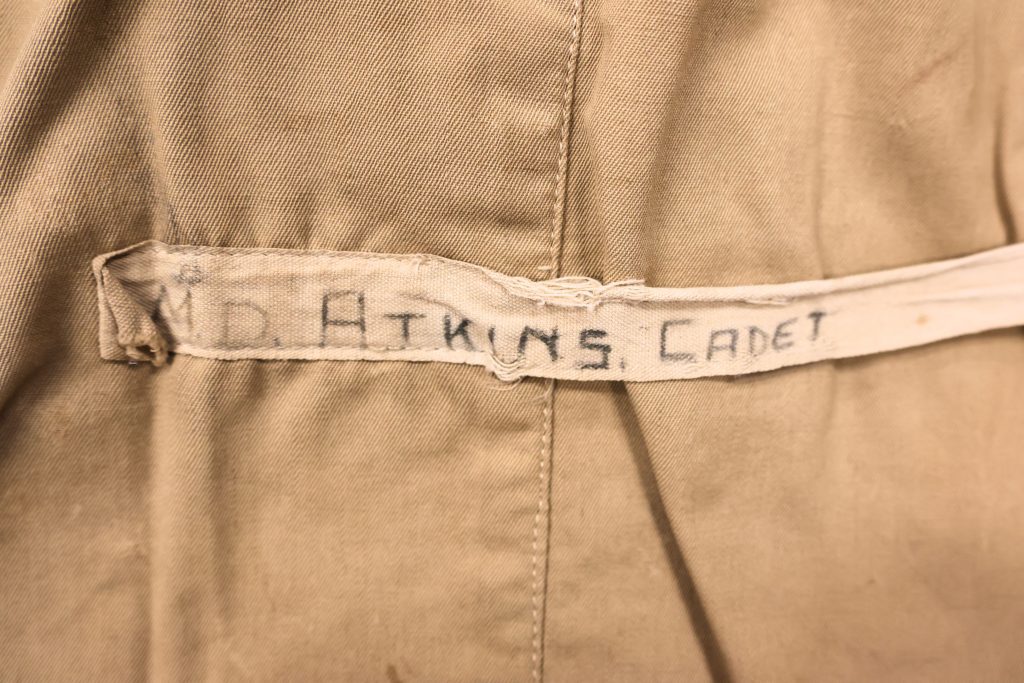

One 96-year-old man who served aboard as an officer cadet was interviewed several times by Black. Entrusting his memories to Black for posterity in print, he eventually also gifted him something he had been carrying since 1942: the life jacket that saved him.

What’s more, he actually had two life jackets to give Black. Atkins also survived the sinking of RMS Empress of Canada in 1943.

Maurice’s Story

This is the story of Maurice Dudley Atkins, raised in Brentwood Bay. Atkins entered HMS Conway, a naval academy in England, as a teen. He was only seventeen years old on February 5, 1942 when a Japanese plane with machine guns blazing faced off with the Empress of Asia near Singapore. Atkins was on the bridge.

More planes dive-bombed the ship, ripping apart the decks and disabling water pumps down below. Fire spread through the vessel. Unable to move from one end of the ship to the other due to the flames and smoke, Atkins put on his life jacket. He and Ordinary Seaman William McKinnon lowered mooring line over the side in loops, so that two men could climb down each loop at the same time and escape the burning ship. Dozens entered the water this way, including Atkins and McKinnon. The life jacket kept Atkins afloat and alive until he could be rescued by a boat.

Survivors were taken to Singapore. Atkins wore the life jacket again when he and many of the Empress of Asia crew escaped on small coastal vessels to avoid becoming prisoners of war when Singapore fell to the Japanese a little over a week later.

It wasn’t this life jacket that Atkins reached for on March 13, 1943 when an Italian submarine sent two torpedoes into the Empress of Canada–it was a newly issued one. His rank was Third Officer, but he was still a teenager at 18.

The Empress of Canada carried civilian refugees, Italian prisoners of war, and military personnel. The ship was abandoned in the early hours of March 14; Atkins helped launch a motorboat as another torpedo struck, and rescued survivors floating around the vessel. Naval ships arrived two days later to rescue them after they were spotted by an amphibious plane.

Tragically, 392 of the nearly 1,530 passengers and 362 crew aboard died in the sinking.

Life jacket from the 1943 sinking of the Empress of Canada.

Black wrote a wonderful account of Atkins’ story in the Victoria Times Colonist last year, explaining that he was searching for a permanent home for these treasured objects in his safekeeping. Atkins became a ship’s captain, worked for Transport Canada, and owned a successful marine services business. He passed away in 2022 at age 97.

Last month, Atkins’ life jackets “came home” to the Maritime Museum of BC collection, where they will be catalogued, photographed, safely stored, and its records digitized in our searchable digital collections catalogue.

Maurice Atkins’ two life jackets, now in their permanent home in the MMBC collection.